Has Labor Force Participation Recovered from the 2020 Recession?

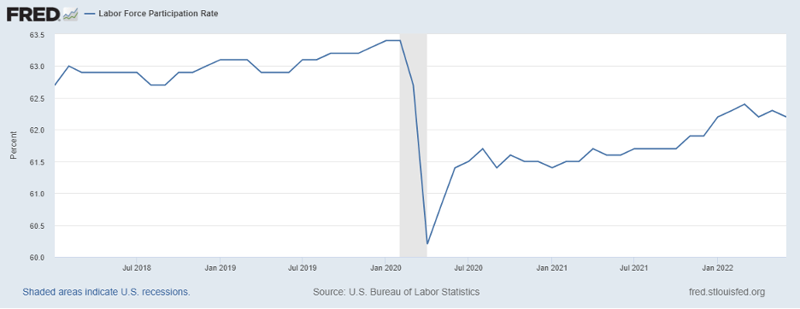

The labor force participation rate has not returned to its pre-pandemic level despite quick recovery in other parts of the economy. The most recent data from June 2022 puts the participation rate at 62.2%, over a full percentage point below the February 2020 level of 63.4%.

Labor force participation rates are used to gauge the health of the economy, so this shortfall is a point of concern. Lower labor force participation can hinder gross domestic product (GDP) growth since fewer individuals are contributing to output, and it can also lead to higher tax rates if the government must withdraw revenue from a smaller tax base.[1]

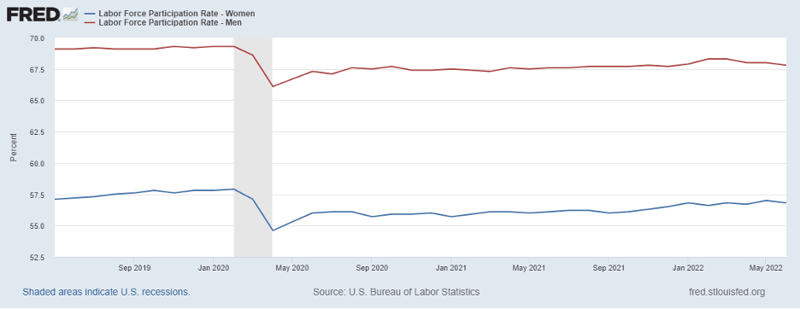

Analyses of participation rates specific to different demographic groups provide possible reasons for this lack of full recovery. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women faced a slightly larger drop in the labor force participation rate during the 2020 recession at a 3.3 percentage point decrease compared to a 3.2 percentage point drop for men.

Many women were driven out of the labor force to adopt caretaking roles due to the disruptions of the pandemic.[2] Growth of the female participation rate accelerated in September 2021, likely reflecting the return of many children to in-person learning at the start of the 2021-2022 school year.

Despite the bigger drop in participation, the rate for women has recovered closer to its pre-pandemic levels than that of men. The current male participation rate (67.8%) is still over a full percentage point away from its pre-pandemic level of 69.3%. Federal pandemic relief funds to households in recent years aimed at boosting economic recovery could have influenced male participation rates. These transfers, like the well-known stimulus checks, are estimated to account for almost 20% of the shortfall in the labor force participation rate between February 2020 and August 2021.[3] As households spend the last of those funds, labor force participation is expected to increase.

Another possible reason individuals have not returned to the labor force is a change in attitudes towards work. The option of remote work introduced improved labor flexibility and influenced how people view the workforce.[4] Research found that the reservation wage, the lowest wage a person would accept to enter the labor market, increased by 6.2% during the pandemic, indicating that higher incentives were needed to entice workers.[5]

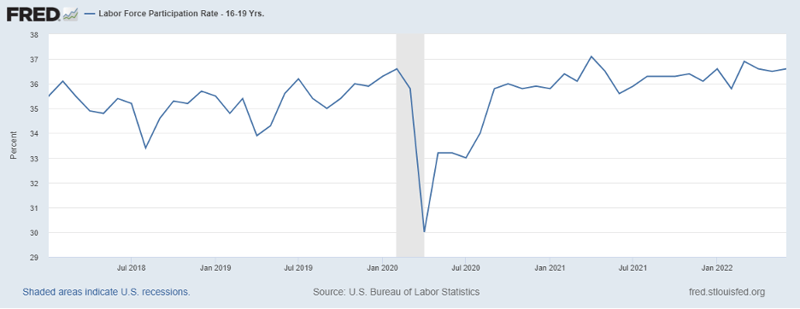

A closer look at the participation rates of different age groups offers additional insights to the shortfall of the overall participation rate to pre-Covid levels.

Younger workers, ages 16-19, faced the sharpest decline in labor force participation rate as shown in the figure below. Despite this fall, their participation had the highest recovery of all age groups and surpassed their pre-pandemic level in March of this year with a rate of 36.9%. This is likely tied to the large number of job openings in industries such as retail and food services where young adults often find work.

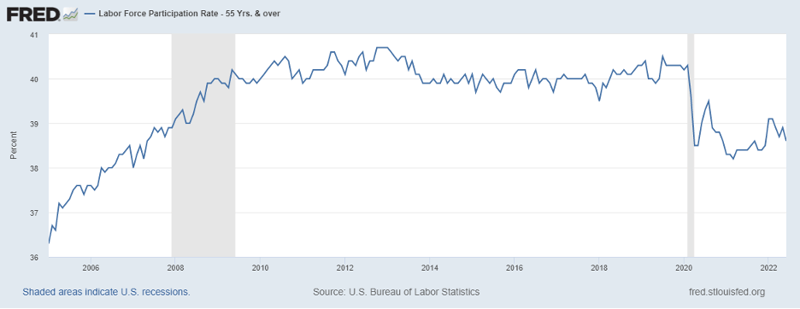

The age group contributing the most to the shortfall of the overall participation rate may be individuals 55 and over. Labor participation of this age group has recovered the least since the start of the pandemic as compared to other ages and is still the furthest from the pre-pandemic rate.

The labor participation rate of those 55 and over has already been on a downward trend as the large baby boom generation has begun approaching retirement age.[6] Many people on the verge of retiring chose to use the pandemic as a spur to early retirement, which has a negative effect on the labor force participation rate as they leave the workforce.

As seen in the graph above, the participation of those 55 and over flattened in 2010 and began declining a few years later. This decline is expected to continue as the retirement rate increases.[7]

It is unlikely that the low participation rate of those 55 and over is solely a retirement issue. One study[8] found that the likelihood of workers 55 & over to leave the workforce increased 7% during the pandemic, while the average retirement rate only increased by 1%. The difference is explained by individuals who stopped working and are not looking for work now (not in the labor force) but who are still open to working again in the future (not retired). This interpretation is supported by the fact that Social Security benefits did not see a large increase in claims following the recession despite an increase in workforce exits.

These labor market exits without strong intent to retire could also partially be explained by support from government transfer payments, worries about workplace safety and contracting Covid-19, or simply uncertainty about the current state of the workforce.

Incentives can encourage individuals to return to the labor market. Higher wages and better labor flexibility (particularly around childcare) may help induce more prime-age (25-54 years old) men and women to reenter the workforce. Time for Covid-19 conditions to improve may be the key to increasing the participation of those over 55 and prime age workers with health risks so they feel more comfortable participating in a work environment again. A looming recession in 2023 may also push participation rates up if more people seek employment in the face of challenging economic conditions.

-----------

[1] Michael Dotsey, Shigeru Fujita, and Leena Rudanko, “Where is Everybody? The Shrinking Labor Force Participation Rate,” Economic Insights 2, no. 4 (2017): 17.

[2] Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh, "Caregiving for children and parental labor force participation during the pandemic," FEDS Notes, Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, November 05, 2021.

[3] Felipe F. Schwartzman, “COVID Transfers Dampening Employment Growth, but Not Necessarily a Bad Thing,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, no. 29-31 (November 2021).

[4] R. Jason Faberman, Andreas I. Mueller, and Ayşegül Şahin, “Has the Willingness to Work Fallen during the Covid Pandemic?” NBER Working Paper, no. 29784 (February 2022): 29-30.

[5] Faberman 27.

[6] A.B. Krueger, “Where have all the workers gone? An inquiry into the decline of the U.S. labor force participation rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2017): 52.

[7] Dotsey, Fujita, and Rudanko, “Where is Everybody?” 21.

[8] Laura D. Quinby, Matthew S. Rutledge, and Gal Wettstein, “How has Covid-19 affected the labor force participation of older workers?” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, WP no. 19, (October 2021): 8-12.

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update

Subscribe to the Weekly Economic Update and get news delivered straight to your inbox.